Are Predictions About Climate Change To Pessimistic?

Abstract

The use of emotion in climate change appeals is a hotly debated topic. Warning virtually the perils of imminent mass extinction, climatic change communicators are oftentimes accused of being unnecessarily 'doomsday' in their attempts to foster a sense of urgency and activeness among the public. Pessimistic messaging, the thinking goes, undermines engagement efforts, straining credulity and fostering a sense of helplessness, rather than concern. Widespread calls for more optimistic climate change messaging punctuate public discourse. This inquiry puts these claims to the test, investigating how affective endings (optimistic vs. pessimistic vs. fatalistic) of climate change appeals impact individual hazard perception and outcome efficacy (i.e., the sense that i's beliefs matters). The findings of three online experiments presented in this paper advise that climatic change appeals with pessimistic affective endings increase risk perception (Studies ane and 2) and outcome efficacy (Study 3), which is the result of heightened emotional arousal (Studies 1–three). Moreover, the results signal that the mediating effect of emotional arousal is more than prevalent amid political moderates and conservatives, as well as those who hold either individualistic or hierarchical world views. Given that these audiences mostly exhibit lower chance perception and outcome efficacy in relation to climate alter, the results suggest that climate change appeals with pessimistic endings could trigger higher engagement with the issue than optimistic endings. These findings are interpreted in calorie-free of recent research findings, which propose that differences in threat-reactivity and emotional arousal may exist owing to brain functions/beefcake mappable to basic motivations for safety and survival. Implications for scholars and practitioners are discussed.

"I don't want your hope. I want you to panic. I desire you to experience the fear I do. Every day. And want you to act. I want yous to behave similar our house is on burn down. Because information technology is."

–Greta Thunberg (World Economic Forum'south Annual Coming together in Davos, 2019)

Introduction

Should climate change appeals take optimistic or pessimistic endings? On the one paw, pessimistic messaging, ofttimes characterized as "climate disaster porn," may be equally harmful to appointment efforts every bit outright denial (Isle of mann et al., 2017) if it fosters paralysis rather than action (Freedman, 2017). On the other hand, though optimistic messaging may comfort a public suffering from chronic 'apocalypse fatigue' (Nordhaus and Shellenberger, 2009), information technology might not spark the melancholia engagement critical for triggering risk perception (Slovic et al., 2004).

Affect is a powerful lever that can cause us to exist overly sensitive to small-scale changes in the environment while distracting us from large shifts of much greater consequence (Slovic et al., 2004). It can prompt irrational levels of alarm regarding threats with low levels of likelihood (Rottenstreich and Hsee, 2001), and deluded levels of optimism in the face up of potentially catastrophic consequences (Sharot, 2011). In the context of climatic change, positive affect leads to avoidance of new information, which could potentially crusade distress, whereas negative affect has the contrary consequence (Yang and Kahlor, 2013). In take a chance management, negative affect is widely acknowledged every bit the "wellspring of action" (Peters and Slovic, 2000), and this has shown to be no less true for the threat of climate alter (Schwartz and Loewenstein, 2017). Such prove diverges from findings in the field of wellness communication, where positive bear upon encourages information-seeking (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, 1995; Yang et al., 2011). One plausible caption for this inverse consequence is perceived efficacy, an important predictor of engagement with climate change (Feldman and Hart, 2015; Kellstedt et al., 2008). In other words, people are less likely to accept action when they feel overwhelmed or hopeless (Bandura, 2002; Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Mayer and Smith, 2019).

Negative bear upon has been shown to increment estimations of adventure probability while positive affect reduces them (Finucane et al., 2000; Ganzach, 2000). In line with the principle of loss aversion (Tversky and Kahneman, 1992), negative touch is more likely to be associated with loss rather than gain frames. A number of studies show that sadness (Schwartz and Loewenstein, 2017), worry (Smith and Leiserowitz, 2014), fear (Feldman and Hart, 2015), anxiety (Weber, 2006), hope, and anger (Feldman and Hart, 2015) are strongly associated with climate change engagement, while others observe no association with anger or fearfulness (Smith and Leiserowitz, 2014). Witte and Allen (2000) find that fear appeals are ineffective when perceived efficacy is low. Moreover, negative affect can exist considered a form of cognitive discomfort, and as the summit end rule illustrates (Do et al., 2008), people are willing to choose situations with objectively more overall pain as long as the event ends with relatively less hurting. For this reason, we focus on how valence at the end of a climate change appeal influences a receiver's risk perception of climate change-related consequences, and their perceived outcome efficacy.

The cess of risk is subjective and inextricably linked to judgments made on the basis of core values; people tend to subconsciously avoid and mistrust data that threatens their identity or values, or which has the potential to cause estrangement from social in-groups (Kahan, 2015). Belief in anthropogenic climate change is associated with liberal credo (McCright et al., 2016) because the acknowledgment that human activity is influencing the climate implies a demand for regulation. Beyond political beliefs, cultural cognition theory stipulates that core values shape information processing and risk assessment along ii dimensions or cultural worldviews: 'group' and 'grid' (Kahan and Braman, 2006). Research suggests that group/grid cultural worldviews predict beliefs about climate change improve than any other individual characteristic (Kahan et al., 2011). The 'group' dimension categorizes people as either 'individualists' or 'communitarians' based on their beliefs about how strongly people are jump to other members of order. The 'grid' dimension describes values near the degree to which an private believes their choices are controlled and limited by their roles within society.

In this paper, we brand 2 propositions. First, the affective ending (i.e., optimistic vs. pessimistic) of climate modify appeals impacts people's run a risk perception and perceived consequence efficacy, which is mediated through emotional arousal. We propose that climate alter appeals with pessimistic endings positively influence climate alter hazard perception and outcome efficacy because they enhance emotional arousal. Second, the forcefulness of the proposed mediated human relationship is attenuated past the values of a bulletin receiver. Nosotros predict a less pronounced effect for those with liberal ideology, including those property communitarian or egalitarian worldviews, than for conservatives and those holding individualist or hierarchical worldviews.

Beyond 3 experiments, we provide support for our propositions. In Study i, we exam the mediating role of emotional arousal on the impact of a climate change text with an optimistic vs. pessimistic ending on risk perception. Information technology is of import to annotation that we practise not equate negative valence with fatalism. The pessimistic catastrophe still presents the possibility of turning things around. Further, we examination the moderating role of political credo. In Report 2, we successfully replicate Report one by using a video stimulus combined with text, increasing the ecological validity of our findings. We too test the moderating role of message receiver values by adding a more nuanced measure of ideological commitments: cultural worldviews (Kahan et al., 2009), in addition to political ideology. Finally, in Written report 3, using a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population, we add a fatalistic condition and introduce outcome efficacy as a dependent measure.

Written report i: The influence of melancholia catastrophe (optimistic vs. pessimistic) on emotional arousal and perception of climate change risk—written stimuli

Experimental design

In Study 1, participants were presented with a climate change text that had either an optimistic or pessimistic ending. In a unmarried-factor (melancholia ending: optimistic (N = 101) vs. pessimistic (North = 99)) between-subjects online experiment (N = 200 U.S.-based residents were recruited through Mturk (35.five% females, M age = 34.6, SDhistoric period = 10.4) for a compensation of USD ane.20. Sample size was adamant beforehand (Simmons et al., 2011) with the goal of having at least 100 participants in each condition. After providing informed consent and demographic background information, participants were randomly assigned to an experimental condition. The two written stimuli were derived from an adaptation of the transcript and photos of a climate change video, differing only in the valence of their endings (see Supplementary Information, Appendix A).

Qualified participants were asked to assess climate alter chance using the item, "How much risk practise you believe global warming poses to human wellness, rubber, or prosperity?" (Kahan, 2017) on an viii-signal Likert scale with anchors from 0 = "none at all" to 7 = "extremely high risk" (M = 5.42, SD = 1.89). To gauge emotional arousal, we adapted a measure from Salgado and Kingo (2017) using the item, "How emotionally intense was it for y'all to read this article?", on a 7-point calibration with anchors from 1 = "minimal emotional intensity" to vii ="maximal emotional intensity" (M = 4.10, SD = ane.58). In a manipulation cheque, participants were asked to rate whether the entreatment ended on a positive or negative note (optimistic: Yard = 4.63, SD = i.49; pessimistic: M = ane.92, SD = 1.04; t(198) = fourteen.94, p < 0.000). Finally, participant political ideology was assessed (47.0% liberals, 30.5% moderates, 22.5% conservatives), every bit well as additional items outside of the focus of this study.

Results

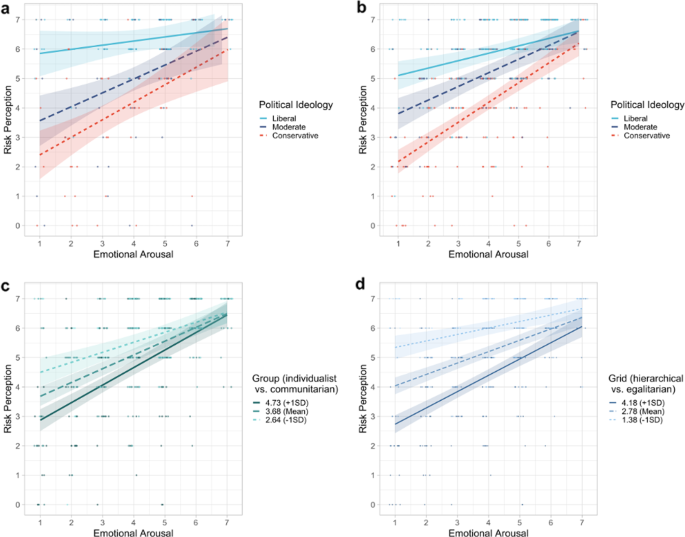

Consistent with our expectations, participants in the pessimistic condition reported greater take chances perception (M = five.66, SD = one.79) than those in the optimistic status (Thousand = v.xx, SE = i.97; Isle of mann–Whitney U = 4244, p = 0.055). Moreover, participants in the pessimistic status reported college emotional arousal (M = 4.44, SD = 1.57) than those in the optimistic status (Thou = 3.75, SD = 1.53; t(198) = −3.17, p = 0.002). A linear regression modelling take chances perception further revealed a significant positive relationship with emotional arousal (β = 0.48, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.16). These findings suggest a possible mediating role of emotional arousal on the relationship between affective ending and risk perception, a suggestion we tested with conditional process analysis using the PROCESS three.ane macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013), decision-making for historic period and gender. The analysis (Model 4; 10,000 bootstrap samples) revealed a pregnant indirect effect (ab = 0.31, SE = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.ten, 0.56). Finally, we tested the moderating effect of political ideology, following a similar modeling approach (Model fourteen; 10,000 bootstrap samples; Tabular array 1). The chastened mediation index for political moderates was not significant (ab = 0.23, SE = 0.16; 95% CI: −0.06, 0.57), whereas the moderated mediation index for conservatives was significant (ab = 0.31, SE = 0.20; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.77). An exam of the conditional indirect effects at different levels of the moderator (Fig. 1a) revealed that at lower levels of emotional arousal, risk perception is significantly lower for participants with conservative political ideology.

Graph (a): Study 1, interaction betwixt risk perception and emotional arousal across moderator levels (political credo: liberal, moderate, conservative). Graph (b): Written report 2, interaction between risk perception and emotional arousal beyond moderator levels (political ideology: liberal, moderate, bourgeois). Graph (c): Written report 3, interaction between risk perception and emotional arousal across moderator levels (Group cultural worldviews: individualists, communitarians). Graph (d): Study three, interaction betwixt chance perception and emotional arousal across moderator (Filigree cultural worldviews: hierarchical, egalitarian).

Study two: The influence of melancholia ending (optimistic vs. pessimistic) on emotional arousal and perception of climate change risk—video stimuli

Experimental design

In a single gene (affective ending: optimistic (N = 228) vs. pessimistic (North = 221)) between-subjects online experiment, 449 U.S.-based residents were recruited through Mturk (49.9% females, M age = 39.8, SDhistoric period = 12.iii) and compensated with USD 1.xx. Sample size was determined beforehand with the goal of increasing the likelihood of recruiting participants with ideologically various political and cultural worldviews. The protocol was similar to Study 1 with the following exceptions: (i) stimuli included the actual video from which transcripts were adapted for written report 1; (2) the two video stimuli were identical except for the final 6 s that were professionally edited: the original video ended with positive valence, and the adjusted version ended with negative valence; and (iii) afterward viewing the video, participants were asked to read the last ii written entreatment segments used in Study 1.

The statement assessing emotional arousal was adapted to the medium, and read, "how emotionally intense was it for you to watch this video?" Iii measures of message receiver values were employed: (a) political ideology (39.9% liberals, 25.4% moderates, 34.seven% conservatives); (b) group worldviews (individualism vs. communitarianism; M = 3.68, SD = 1.05); and (c) grid worldviews (hierarchy vs. egalitarianism; Thou = 2.78, SD = 1.40). The ii dimensions of cultural worldviews were assessed using the short-grade of the cultural worldview scale (Kahan et al., 2010) (meet Supplementary Information, Appendix B). Finally, in a manipulation cheque, participants were asked to rate whether the appeal ended on a positive or negative notation (optimistic: M = 4.84, SD = ane.41; pessimistic: M = ii.53, SD = ane.33, t(447) = 17.85, p < 0.000).

Results

Consistent with our expectations, participants in the pessimistic status reported greater take chances perception (M = 5.56, SD = ane.53) than those in the optimistic condition (Thousand = 5.17, SD = i.83; Mann–Whitney U = 22329, p = 0.032). More than, participants in the pessimistic condition reported higher emotional arousal (M = iv.49, SD = i.57) than those in the optimistic condition (One thousand = 4.02, SD = 1.67; t(447) = −3.08, p = 0.002). A linear regression modelling adventure perception farther revealed a significant positive relationship with emotional arousal (β = 0.54, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001; R 2 of 0.27). Following an belittling approach similar to Study ane, nosotros tested the mediating effect of emotional arousal. The analysis revealed a significant indirect result (ab = 0.25, SE = 0.08; CI = 0.09, 0.41). Finally, we tested the moderating furnishings of political ideology, grouping, and grid cultural worldviews. All chastened mediation indices were significant (Table 1). An examination of the conditional indirect furnishings at different levels of the moderators (Fig. 1b–d) revealed that at lower levels of emotional arousal, risk perception is significantly lower for moderates and conservatives, too as for lower levels of group and grid values (i.e., communitarians and egalitarians, respectively).

Give-and-take: Studies i and 2

The results of the first two studies provide support for our proposition that climate change appeals with a pessimistic ending trigger emotional arousal, which in plough influences perceptions of climate change risk. Moreover, the influence of emotional arousal on chance perception differs across people with varying political ideologies and cultural worldviews. The greatest differences are observed among conservatives and people holding individualist or hierarchical worldviews, who report higher levels of business about climatic change when presented with a pessimistic climate change appeal.

Written report 3: the influence of affective ending (optimistic vs. pessimistic vs. fatalistic) on emotional arousal, climate change take a chance perception, and consequence efficacy

Experimental design

In Studies ane and 2, we tested the two poles of affective catastrophe (optimistic vs. pessimistic). Prior work suggests that people are more than receptive to information when both threat appraisal and result efficacy are high (Witte and Allen, 2000). People might be scared into perceiving risk, but how does this influence the sense that their own actions matter for solving the challenge of climate change? Thus, in Study three, we added a third condition to test the deviation between negative affective valence arising from pessimistic messaging with the possibility of a hopeful outcome (pessimistic status) versus fatalistic messaging suggesting that it is likewise tardily to plough things effectually (fatalistic status). Moreover, we introduced perceived event efficacy equally a dependent measure to exam the suggestion that both negative atmospheric condition would outperform positive valence for sparking emotional arousal, motivating a stronger sense of agency and influence on outcomes related to climatic change. Finally, we used a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population to increment the external validity of our findings.

In a single factor, between-subjects online experiment, 1115 U.s.a.-based residents (54.three% females; M historic period = 49.8, SDage = 16.8) were recruited through a nationally representative panel. Sample size was determined beforehand. The protocol and measures were similar to the two previous studies with the following exceptions: (i) in addition to optimistic (N = 375) and pessimistic (N = 375) weather condition, a fatalistic condition was added (North = 365) (Supplementary Information, Appendix C); (2) the main dependent variable, effect efficacy, was operationalized using a single item, "I believe my deportment have an influence on climate change" adapted from Kellstedt et al. (2008), and measured on a four-point calibration with anchors 1 ="strongly disagree" to 4 ="strongly agree") (M = 2.91, SD = 0.99); and (c) the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale was included to measure trait efficacy35 consisting of x items measured on a 4-signal scale with anchors 1 ="not at all true" to 4 ="exactly true") (G = 3.18, SD = 0.48; α = 0.xc). The aforementioned message receiver values were employed as in Study two: (a) political ideology (31.6% liberals, 35.2% moderates, 33.3% conservatives) (b) group cultural worldviews (individualism vs. communitarianism; M = 4.05, SD = 1.14), and (c) filigree cultural worldviews (hierarchy vs. egalitarianism; Grand = 3.05, SD = 1.threescore). Finally, in a manipulation cheque, participants were asked to charge per unit whether the appeal ended on a positive or negative note (F(ii,1112) = lxx.63, p < 0.001). Mail hoc comparisons using Tukey'southward HSD test revealed that the optimistic condition was rated equally more positive (One thousand = iv.52, SD = 1.66) than the pessimistic ending status (M = 3.36, SD = one.92, p < 0.001), with the latter being more than positive than the fatalistic condition (M = 2.98, SD = i.93, p = 0.014).

Results

We did not detect any pregnant difference in outcome efficacy beyond the three conditions (F(2,1112) = 0.27, p = 0.761), still, we did observe meaning differences in emotional arousal, (F(2,1112) = 8.34, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons using Tukey's HSD test revealed that participants in the pessimistic status reported higher emotional arousal (M = 3.69, SD = 1.84) than those in the optimistic condition (K = 3.22, SD = 1.89; p < 0.001). However, there was no meaning difference betwixt the pessimistic and fatalistic conditions (M = 3.74, SD = 1.99; p = 0.920). A linear regression with event efficacy as the dependent variable further revealed a significant positive association with emotional arousal (β = 0.22, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001; R ii of 0.18).

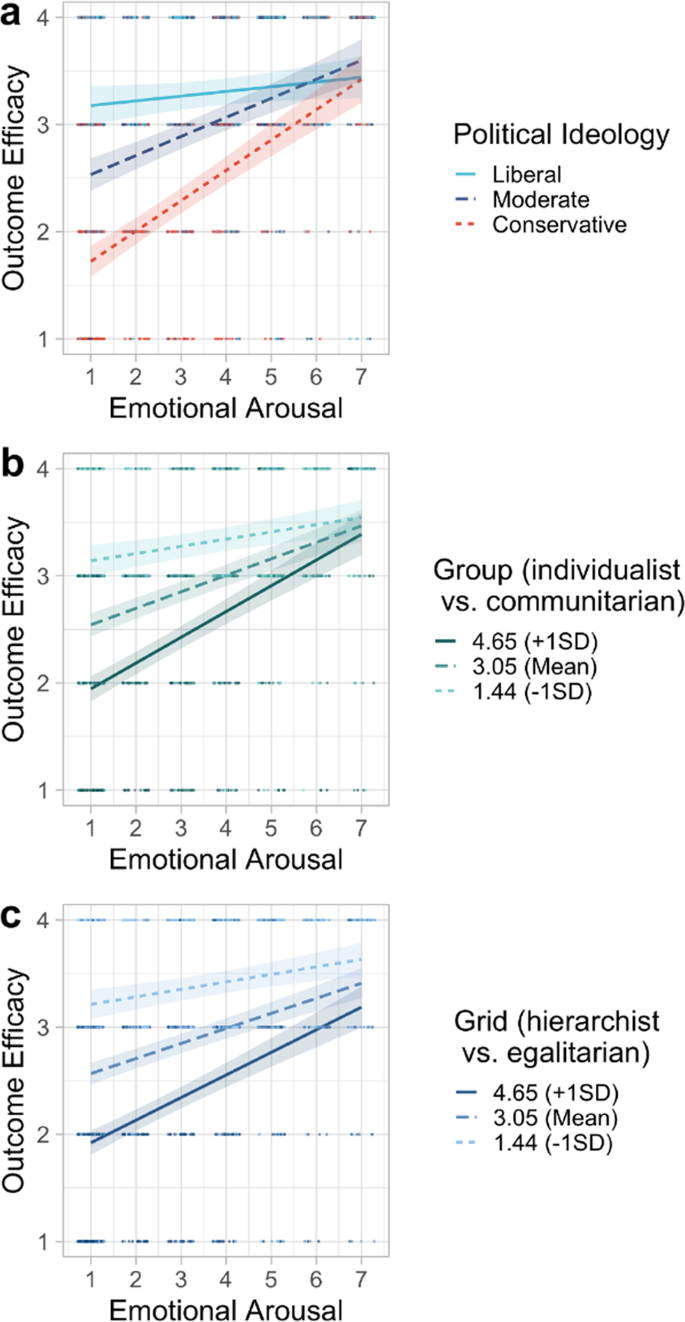

Next, we tested the mediating result of emotional arousal on the relationship between melancholia catastrophe and result efficacy, using provisional process assay controlling for historic period, gender, and trait efficacy. Assay revealed significant indirect effects for the pessimistic (ab = 0.09, SE = 0.03; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.fifteen), and fatalistic atmospheric condition (ab = 0.x, SE = 0.03; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.17). We and so tested the moderating role of core values, operationalized equally political ideology, group-, and filigree cultural worldviews. All tested moderated arbitration indices were meaning (Table ii). An examination of the provisional indirect effects at unlike levels of the moderators (Fig. 2) revealed that perceived event efficacy is lower at lower levels of emotional arousal for all groups, just the upshot is particularly pronounced for moderates and conservatives, every bit well as for those with lower levels of group and grid values (i.eastward., communitarians and egalitarians).

Interaction furnishings between risk perception and emotional arousal across groups of moderators.

Give-and-take: Study 3

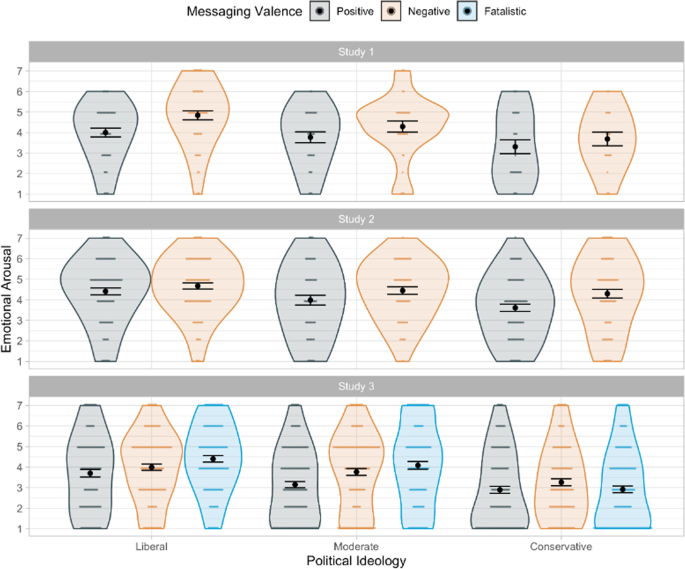

The results of Study 3 successfully replicate the findings of the two previous studies with a different dependent variable: event efficacy. As in Studies 1 and 2, the divergence in outcome efficacy as a result of increased emotional arousal was significantly greater in groups most likely to be disengaged with the issue, namely moderates and conservatives, and those holding communitarian and egalitarian cultural worldviews (Figs. 2 and 3).

Violin plots of experienced emotional arousal past condition and political ideology, Studies 1–iii. Black dots represent means; error bars bespeak standard errors.

General discussion

Our findings suggest that the affective ending of climate modify appeals influences date. Pessimistic endings yield higher take a chance perception via heightened emotional arousal, and though this held truthful for all audiences, the furnishings are specially pronounced in individuals usually exhibiting low-levels of concern about climate change (i.eastward., moderates, conservatives, and those holding individualistic or hierarchical worldviews). Optimistic endings may comfort a public suffering from apocalypse fatigue, but do not appear to increase risk perception and perceived result efficacy. These findings are in line with recent experimental work finding that cardiac activity indicative of emotional arousal predicts behavioral appointment with climate modify (Morris et al., 2019). In contrast to work positing that "fright appeals" may hinder efficacy (O'Neill and Nicholson-Cole, 2009), our results also suggest that pessimistic endings actually increment people's belief that their own private behavior matters for climatic change, even in the face of fatalistic messaging, though at that place are differences across ideologically diverse groups.

Research from the fields of neuroscience and social psychology offers plausible explanations for why conservatives might exist more than threat-reactive in the face of emotional arousal than liberals. While the formation and processing of emotion involve complex neural connectivity, there is evidence for the lateralization (asymmetrical representation) of brain office Lane and Nadel (2002). Liberalism has been associated with increased greyness matter book in the inductive cingulate cortex, an area of the brain associated with emotion regulation and executive role, which allows for greater cognitive flexibility (Kanai et al., 2011). Conservativism, on the other hand, has been associated with increased volume in the correct hemisphere of the amygdala (Amodio et al., 2007; Kanai et al., 2011), an area which exerts greater influence on the processing of primary emotions such equally fear, also as emotional expression than the left hemisphere. These differences in brain functions/beefcake may exist mappable to basic motivations for safe and survival and explain the association between political credo and threat reactivity (Lilienfeld and Latzman, 2014; Pedersen et al., 2018). Napier et al. (2018) found, for example, that Republicans took significantly more liberal positions on social issues after envisioning feeling completely and totally physically prophylactic, while Nail et al. (2009) found that dispositional liberals took on considerably more conservative positions in the face of arrangement-injustice and mortality salience threats.

These findings affirm the disquisitional role of negative affect as a powerful lever for heightening perception of climatic change run a risk but require farther investigation. Climate change scholars, communicators, and policymakers should examination segmentation strategies to assess the optimal degree of negativity in messaging designed for ideologically—and culturally diverse audiences. Given that public engagement with climate change is low in the U.s. (Leiserowitz et al., 2017), and even in Europe, very few people feel a sense of personal responsibility for its effects (European Committee, 2014), 1 possible remedy could be to tailor the affective ending of climate change appeals.

What are the long-term effects of various melancholia combinations on adventure perception and efficacy, and do these effects persist over time? Exercise these vary beyond cultures? At what indicate might the use of negative bear on backlash every bit a result of desensitization? These are important questions worth exploring in hereafter work.

Ethics statement

The work was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Announcement, taking every precaution to protect the privacy and interests of human participants, all of whom gave written, informed consent.

Information availability

The datasets for the iii studies analyzed in this manuscript have been registered with the Open Science Framework. Complete stimulus materials are available in the Supplementary Information, and data can be accessed with permission from Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/bvqat/?view_only=455db4ac6b744393920a1e056ddac8d1.

References

-

Amodio DM, Jost JT, Master SL, Yee CM (2007) Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism. Nat Neurosci x(10):1246–1247

-

Bandura A (2002) Social foundations of thought and action. In D. F. Marks (Ed.), The health psychology reader (pp. 94–106). SAGE Publications Ltd, London. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221129.n6

-

Do AM, Rupert AV, Wolford G (2008) Evaluations of pleasurable experiences: the Acme-End Rule. Psychon Bull Rev 15(1):96–98

-

European Commission (2014) Climatic change, Special barometer. European Commission. http://ec.europa.european union/public_opinion/athenaeum/ebs/ebs_409_en.pdf

-

Feldman L, Hart PS (2015) Using political efficacy letters to increase climate activism: the mediating role of emotions. Sci Commun 38(one):99–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015617941

-

Finucane ML, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson SM (2000) The touch heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J Behav Decis Mak xiii(1):one–17

-

Freedman A (2017) No, New York Magazine: climate change won't make the world uninhabitable by 2100. Mashable. https://mashable.com/2017/07/10/new-york-mag-climate-story-inaccurate-doomsday-scenario/?europe=true#Qr0U8y0_wPqE

-

Ganzach Y (2000) Judging risk and return of financial assets. Organ Behav Hum Decision Process 83(2):353–370

-

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process assay: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York

-

Kahan DM (2015) Climate‐science communication and the measurement problem. Political Psychol 36(S1):1–43. https://doi.org/x.1111/pops.12244

-

Kahan DM (2017) 'Ordinary science intelligence': a science-comprehension measure for written report of chance and science communication, with notes on evolution and climate change. J Risk Res 20(8):995–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1148067

-

Kahan DM, Braman D (2006) Cultural cognition and public policy. Yale Law Policy Rev 24(1):149–172

-

Kahan DM, Braman D, Cohen GL, Gastil J, Slovic P (2010) Who fears the hpv vaccine, who doesn't, and why? An experimental study of the mechanisms of cultural noesis. Law Hum Behav 34(6):501–516

-

Kahan DM, Braman D, Slovic P, Gastil J, Cohen One thousand (2009) Cultural cognition of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Nat Nanotechnol four(two):87

-

Kahan DM, Jenkins-Smith H, Braman D (2011) Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J Risk Res 14(two):147–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

-

Kanai R, Feilden T, Firth C, Rees Thousand (2011) Political orientations are correlated with brain construction in young adults. Current biological science 21(viii):677–680

-

Kellstedt PM, Zahran S, Vedlitz A (2008) Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climatic change in the United States. Adventure Anal 28(1):113–126

-

Lane RD, Nadel 50 (2002) Cognitive neuroscience of emotion. Oxford University Press

-

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal Due south, Cutler One thousand, Kotcher J (2017) Climate modify in the American Mind: Oct 2017. Yale program on climate change communication. Yale Academy and George Stonemason University, New Haven, CT

-

Lilienfeld SO, Latzman RD (2014) Threat bias, not negativity bias, underpins differences in political ideology. Behav Encephalon Sci 37(iii):318–319

-

Lorenzoni I, Nicholson-Cole S, Whitmarsh L (2007) Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change amongst the United kingdom public and their policy implications. Glob Environ Change 17(3–4):445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

-

Mann ME, Hassol SJ, Toles T (2017) Doomsday scenarios are as harmful every bit climate change denial. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/doomsday-scenarios-are-as-harmful-as-climate-alter-denial/2017/07/12/880ed002-6714-11e7-a1d7-9a32c91c6f40_story.html

-

Mayer A, Smith EK (2019) Unstoppable climate modify? The influence of fatalistic beliefs well-nigh climate alter on behavioural change and willingness to pay cross-nationally. Clim Policy nineteen(iv):511–523

-

McCright AM, Dunlap RE, Marquart-Pyatt ST (2016) Political credo and views most climate change in the European Wedlock. Environ Politics 25(two):338–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1090371

-

Morris BS, Chrysochou P, Christensen J, Orquin J, Barraza JA, Zak PJ, Mitkidis P (2019) Stories vs. facts: triggering visceral response to climate change. Clim Change

-

Blast PR, McGregor I, Drinkwater AE, Steele GM, Thompson AW (2009) Threat causes liberals to think like conservatives. J Exp Soc Psychol 45(4):901–907

-

Napier JL, Huang J, Vonasch AJ, Bargh JA (2018) Superheroes for alter: physical safety promotes socially (but not economically) progressive attitudes among conservatives. Eur J Soc Psychol 48(2):187–195

-

Nordhaus T, Shellenberger M (2009) Apocalypse fatigue: losing the public on climate modify. Yale Environ 360:xvi

-

O'Neill S, Nicholson-Cole S (2009) "Fear won't do information technology" promoting positive engagement with climatic change through visual and iconic representations. Sci Commun 30(iii):355–379

-

Pedersen WS, Muftuler LT, Larson CL (2018) Conservatism and the neural circuitry of threat: economical conservatism predicts Greater Amygdala–Bnst connectivity during periods of threat vs. safety. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 13(ane):43–51

-

Peters E, Slovic P (2000) The springs of action: affective and analytical information processing in choice. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 26(12):1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002612002

-

Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK (2001) Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci 12(3):185–190

-

Salgado Due south, Kingo OS (2019) How is physiological arousal related to self-reported measures of emotional intensity and valence of events and their autobiographical memories? Witting Cogn 75:102811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2019.102811

-

Schwartz D, Loewenstein Yard (2017) The chill of the moment: emotions and proenvironmental behavior. J Public Policy Market 36(2):255–268

-

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem K (1995) Generalized self-efficacy scale measures in health psychology: a user's portfolio. causal and control beliefs. NFER-Nelsen, Windsor, pp. 35–37

-

Sharot T (2011) The optimism bias. Curr Biol 21(23):R941–R945

-

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U (2011) False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Drove and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything equally Significant. Psychol Sci 22(eleven):1359–1366. https://doi.org/x.1177/0956797611417632

-

Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters Eastward, MacGregor DG (2004) Risk as analysis and risk every bit feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, gamble, and rationality. Risk Anal 24(ii):311–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.10

-

Smith N, Leiserowitz A (2014) The part of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Anal 34(5):937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140

-

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1992) Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J Risk Uncertain v(4):297–323

-

Weber EU (2006) Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term adventure: why global warming does not scare us (all the same). Clim Alter 77(1):103–120

-

Witte K, Allen M (2000) A meta-analysis of fearfulness appeals: implications for constructive public wellness campaigns. Health Educ Behav 27(v):591–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700506

-

Yang ZJ, Kahlor L (2013) What, me worry? The role of affect in information seeking and avoidance. Sci Commun 35(2):189–212

-

Yang ZJ, McComas KA, Gay G, Leonard JP, Dannenberg AJ, Dillon H (2011) Information seeking related to clinical trial enrollment. Commun Res 38(6):856–882

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank David Salvesen and the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill for sharing so generously from NC Climate Stories, from which our experimental stimuli were created. Thanks also to Jacob D. Christensen and Jacob L. Orquin for their helpful comments throughout this piece of work. We are also enormously grateful for the support this research has received in the class of seed funding from the Interacting Minds Centre, Aarhus University, also equally the Aarhus University Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'due south annotation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you lot give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary party material in this article are included in the article's Artistic Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended utilize is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilise, you volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Morris, B.S., Chrysochou, P., Karg, S.T. et al. Optimistic vs. pessimistic endings in climatic change appeals. Humanit Soc Sci Commun seven, 82 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00574-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00574-z

Further reading

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-00574-z

Posted by: wynngrecond.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Are Predictions About Climate Change To Pessimistic?"

Post a Comment